7 April Fool’s Day Pranks To Play On Your Friends’ PC http://t.co/KAcEbltOsH

— Mr. Walker (@greshamhs) March 31, 2014

A Lifelong Learner Shares Thoughts About Education

7 April Fool’s Day Pranks To Play On Your Friends’ PC http://t.co/KAcEbltOsH

— Mr. Walker (@greshamhs) March 31, 2014

Article from The Verge

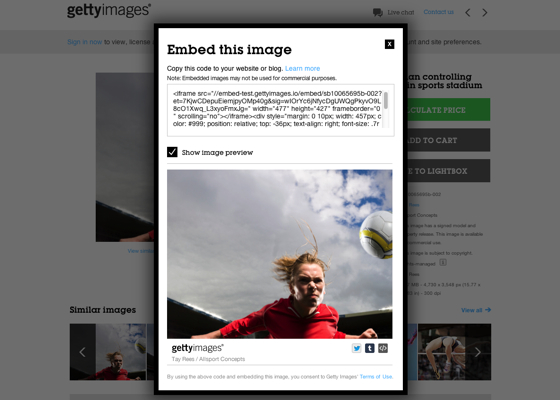

If you go to the Getty Images website, you’ll see millions of images, all watermarked. There are more than a hundred years of photography here, from FDR on the campaign trail to last Sunday’s Oscars, all stamped with the same transparent square placard reminding you that you don’t own the rights. If you want Getty to take off the watermark, you’ll have to pay for it.

"OUR CONTENT WAS EVERYWHERE ALREADY."

Starting now, that’s going to change. Getty Images is dropping the watermark for the bulk of its collection, in exchange for an open-embed program that will let users drop in any image they want, as long as the service gets to append a footer at the bottom of the picture with a credit and link to the licensing page. For a small-scale WordPress blog with no photo budget, this looks an awful lot like free stock imagery.

It’s a real risk for the company, since it’s easy to screenshot the new versions if you want to snag an unlicensed version. But according to Craig Peters, a business development exec at Getty Images, that ship sailed long ago. "Look, if you want to get a Getty image today, you can find it without a watermark very simply," he says. "The way you do that is you go to one of our customer sites and you right-click. Or you go to Google Image search or Bing Image Search and you get it there. And that’s what’s happening… Our content was everywhere already."

THE NEW EMBEDS STRIKE DIRECTLY AT SOCIAL SHARING

Looking at the pictures on Twitter, it’s hard to disagree. Wildly popular accounts like @historyinpics can amass hundreds of thousands of followers with nothing but uncredited, unlicensed images, and since there’s no direct revenue, there’s little point in asking them to pay. At that scale, anything more expensive than free is a prohibitive cost. The new embeds strike directly at that kind of social sharing, with native code for sharing in Twitter and Tumblr alongside the traditional WordPress-friendly embed code. Peters’ bet is that if web publishers have a legal, free path to use the images, they’ll take it, opening up a new revenue stream for Getty and photographers.

The new money comes because, once the images are embedded, Getty has much more control over the images. The new embeds are built on the same iframe code that lets you embed a tweet or a YouTube video, which means the company can use embeds to plant ads or collect user information. "We’ve certainly thought about it, whether it’s data or it’s advertising," Peters says, even if those features aren’t part of the initial rollout.

THE DIGITAL SHIFT HAS BEEN HARD ON PHOTOGRAPHERS

The clear comparison is the music industry, which was hit hard by piracy in the ’90s and took decades to respond. "Before there was iTunes, before there was Spotify, people were put in that situation where they were basically forced to do the wrong thing, sharing files," Peters says. Now, if an aspiring producer wants to leak a song to the web but keep control of it, they can drop it on Soundcloud. Any blog can embed the player, and the artist can disable it whenever they want. And as Google has proved with YouTube, it’s easy to drop ads or "buy here" links into that embed. "We’ve seen what YouTube’s done with monetizing their embed capabilities," Peters says. "I don’t know if that’s going to be appropriate for us or not." But as long as the images are being taken as embeds rather than free-floating files, the company will have options.

EMBEDS HAVE ENABLED A NEW KIND OF LINK ROT

Getty Images’ profits haven’t cratered like music conglomerates: its profits actually increased nearly $100 million from 2007 to 2011, thanks in part to digital licensing. Still, the digital shift has been hard on photographers, with professional stipends increasingly replaced by smaller payments to amateur or freelance photographers. Part of Peters’ promise is that the new embeds will open up larger flows of money down the road.

The biggest effect might be on the nature of the web itself. Embeds from Twitter and YouTube are already a crucial part of the modern web, but they’ve also enabled a more advanced kind of link rot, as deleted tweets and videos leave holes in old blog posts. If the new embeds take off, becoming a standard for low-rent WordPress blogs, they’ll extend that webby decay to the images themselves. On an embed-powered web, a change in contracts could leave millions of posts with no lead image, or completely erase a post like this one.

Still, such long-term effects are years away, if they happen at all. In the meantime, Getty Images is focused on the more immediate problem of infringement. "The principle is to turn what’s infringing use with good intentions, turning that into something that’s valid licensed use with some benefits going back to the photographer," says Peters, "and that starts really with attribution and a link back."

This post originally appeared on James Clear’s blog.

In 2010, Dave Brailsford faced a tough job.

No British cyclist had ever won the Tour de France, but as the new General Manager and Performance Director for Team Sky (Great Britain’s professional cycling team), Brailsford was asked to change that.

His approach was simple.

Brailsford believed in a concept that he referred to as the “aggregation of marginal gains.” He explained it as “the 1 percent margin for improvement in everything you do.” His belief was that if you improved every area related to cycling by just 1 percent, then those small gains would add up to remarkable improvement.

They started by optimizing the things you might expect: the nutrition of riders, their weekly training program, the ergonomics of the bike seat, and the weight of the tires.

But Brailsford and his team didn’t stop there. They searched for 1 percent improvements in tiny areas that were overlooked by almost everyone else: discovering the pillow that offered the best sleep and taking it with them to hotels, testing for the most effective type of massage gel, and teaching riders the best way to wash their hands to avoid infection. They searched for 1 percent improvements everywhere.

Brailsford believed that if they could successfully execute this strategy, then Team Sky would be in a position to win the Tour de France in five years time.

He was wrong. They won it in three years.

In 2012, Team Sky rider Sir Bradley Wiggins became the first British cyclist to win the Tour de France. That same year, Brailsford coached the British cycling team at the 2012 Olympic Games and dominated the competition by winning 70 percent of the gold medals available.

In 2013, Team Sky repeated their feat by winning the Tour de France again, this time with rider Chris Froome. Many have referred to the British cycling feats in the Olympics and the Tour de France over the past 10 years as the most successful run in modern cycling history.

And now for the important question: what can we learn from Brailsford’s approach?

It’s so easy to overestimate the importance of one defining moment and underestimate the value of making better decisions on a daily basis.

Almost every habit that you have — good or bad — is the result of many small decisions over time.

And yet, how easily we forget this when we want to make a change.

So often we convince ourselves that change is only meaningful if there is some large, visible outcome associated with it. Whether it is losing weight, building a business, traveling the world or any other goal, we often put pressure on ourselves to make some earth-shattering improvement that everyone will talk about.

Meanwhile, improving by just 1 percent isn’t notable (and sometimes it isn’t evennoticeable). But it can be just as meaningful, especially in the long run.

And from what I can tell, this pattern works the same way in reverse. (An aggregation of marginal losses, in other words.) If you find yourself stuck with bad habits or poor results, it’s usually not because something happened overnight. It’s the sum of many small choices — a 1 percent decline here and there — that eventually leads to a problem.

Inspiration for this image came from a graphic in The Slight Edge by Jeff Olson.

In the beginning, there is basically no difference between making a choice that is 1 percent better or 1 percent worse. (In other words, it won’t impact you very much today.) But as time goes on, these small improvements or declines compound and you suddenly find a very big gap between people who make slightly better decisions on a daily basis and those who don’t. This is why small choices (“I’ll take a burger and fries”) don’t make much of a difference at the time, but add up over the long-term.

On a related note, this is why I love setting a schedule for important things, planning for failure, and using the “never miss twice” rule. I know that it’s not a big deal if I make a mistake or slip up on a habit every now and then. It’s the compound effect of never getting back on track that causes problems. By setting a schedule to never miss twice, you can prevent simple errors from snowballing out of control.

Success is a few simple disciplines, practiced every day; while failure is simply a few errors in judgment, repeated every day.

—Jim Rohn

You probably won’t find yourself in the Tour de France anytime soon, but the concept of aggregating marginal gains can be useful all the same.

Most people love to talk about success (and life in general) as an event. We talk about losing 50 pounds or building a successful business or winning the Tour de France as if they are events. But the truth is that most of the significant things in life aren’t stand-alone events, but rather the sum of all the moments when we chose to do things 1 percent better or 1 percent worse. Aggregating these marginal gains makes a difference.

There is power in small wins and slow gains. This is why average speed yields above average results. This is why the system is greater than the goal. This is why mastering your habits is more important than achieving a certain outcome.

Where are the 1 percent improvements in your life?

The best test scores don’t always mean the happiest kids at school. The Best Schools and the Happiest Kids visualizes the results from a worldwide survey of over 500,000 15-year-olds globally.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s triennial international survey compared test scores from 65 countries. Happiness was ranked based on the percentage of students who agreed or disagreed with the statement “I feel happy at school.” Test scores were ranked based on the combined individual rankings of the students’ math, reading, and science scores.

I can’t tell for sure, but it appears that Jake Levy, Data Analyst at BuzzFeed created this data visualization based on the data from OECD survey results. Infographics like these often get shared without the rest of the article, so it’s important to include all of the necessary framing information in the graphics itself. Title, descriptive text, sources, URL, publishing company, copyright, etc.

Thanks to Ron Krate on Google+ for posting